Vichy is a resort town of 30,000, best known as the seat of the French government that collaborated with the German Fascists during WWII. However, Vichy had always been a resort town known for its waters. The town prospered when Romans came to take the waters in the first century AD. Louis XVI upgraded the facilities in 1787. I tried the waters, which had a foul, sulfurous taste. The racing course was on the Allier River, in the middle of the town. Resort hotels lined the course.

We drew West Germany for the opening race. We were 1.5 seconds ahead at 1000 meter mark, but they rowed through us decisively, winning by 5 seconds. As winners they advanced to the finals. We went to the Repechage, French for “repeat chance.” We beat Czechoslovakia by nearly 9 seconds and advanced to the final. On the day of the final I noticed that Harry had moved the buttons outboard on the oar. The location of the button determines the fulcrum point of the oar. This change would give us a little more leverage, a lighter load, and less power. A change of 1/4-1/2 inch on a 12-and-1/2 foot oar can be noticeable. We rowed down to the starting line with the other crews. We rowed by sixes and then by eights. We practiced rowing thirty strokes at a racing cadence. At the starting line the athletes took off their warmup suits, display- ing all 54 rowers in their national racing uniforms, with the vari- ous colors of the rainbow displayed. The oarsmen were chattering in their native tongues. The race commands were given in French, the language of FISA, the international rowing association.

The starter checked with each crew:

“Allemand de l’ouest, prêt?” “Soviétiques, prêt?” “États-Unis, prêt?” “Allemand de l’est, prêt?” “Hollande, prez?,” “Australie, prêt?”

Each coxswain raised a hand to acknowledge the boat was aligned and ready.

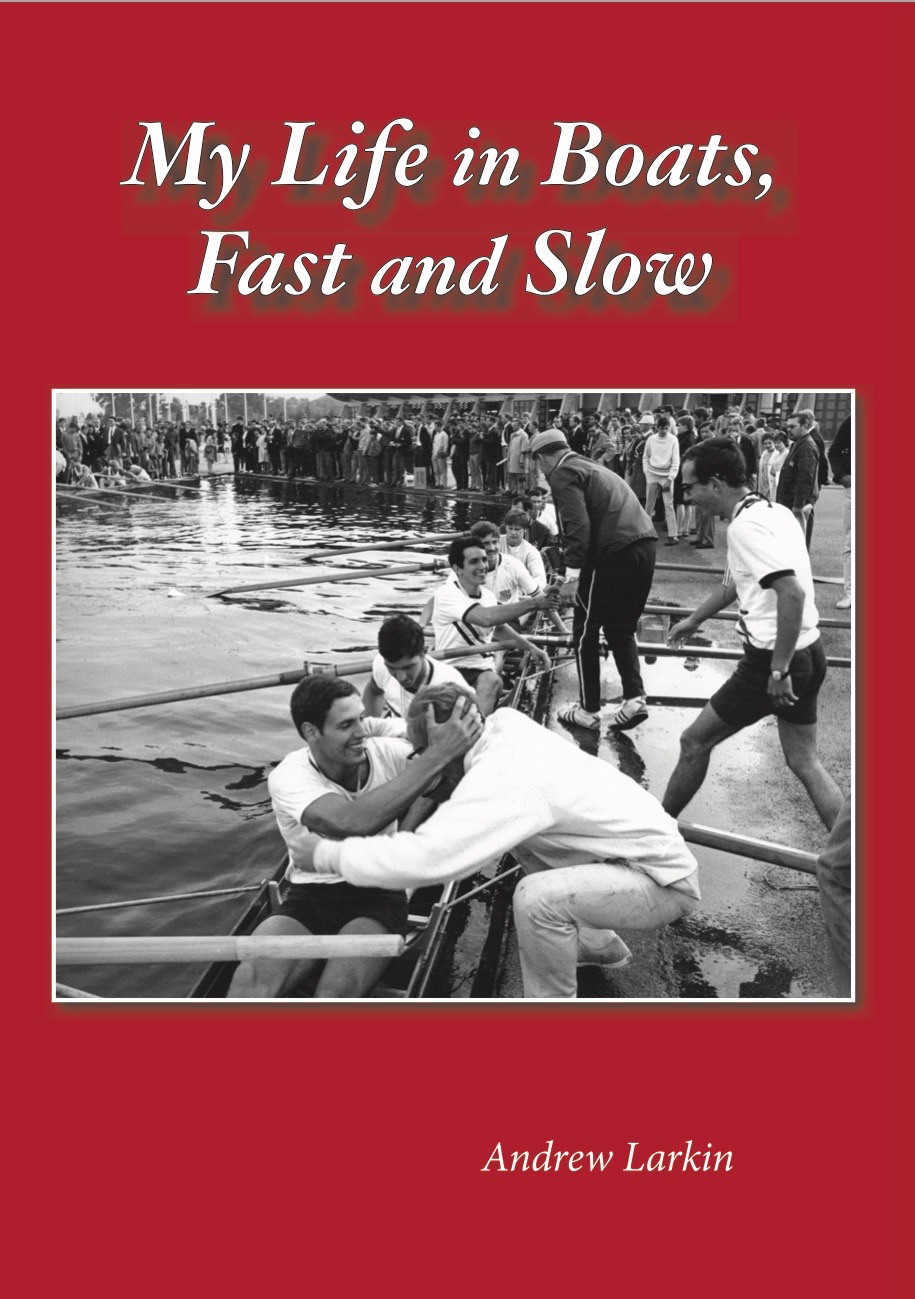

Then the starter declared: “Êtes-vous prêt?”…pause…”Partêz!” All six crews started at once. The tension was released. The mass start began. We got off to a good start. At the 500 meter mark, West Germany, East Germany, USSR, and USA were tied for first at 1:27.69. However, at 1000 meter we had fallen to last place, over six-seconds off pace, out of the race. Yet, there are transcendent times, when everything falls into place. This was to be one such time. The boat became faster in this race than it ever had been in practice. The boat became more than the sum of the parts and the whole developed a power of its own. We were still fresh. We rose to the challenge. We went from last place to second place with 500 meters to go, 3 seconds behind West Germany, 1.5 seconds ahead of the Soviets. In the last 500 meters the Soviets made a move and passed us, but we responded and passed them, closing rapidly on the West Germans, who won, and we finished in second place, 1.5 seconds behind, and 0.03 seconds ahead of the Soviets. We were a college crew, in our early 20’s. We had played with the adults, and proven that we had a right to be there. We were ecstatic. Next year was an Olympic year. Only one person, Jake Fiechter, was graduating. Our hopes were high.

Harry’s comments (from the same newsletter) after the race were:

We did what we wanted to do. We rowed a whole race extremely well under intense pressure. Even in defeat it was a remarkable performance. This outfit deserves to be ranked with any college crew that ever rowed.

Curt Canning wrote “The Longest Summer” for the Dartmouth

Football Game Program (10/67):

Then we were at the 500-to-go mark and everything was taking on finality. The Russian coxswain went crazy. I was wrenched out of my concentration by his incredible yelling. TheRussians were sprinting. They too were trying to catch us. It was our turn to go up. Mind and body screamed for mercy but the sprint was upon us. The next thing I remember was looking over at the Russian seven man as we crossed the line. As I slumped into a numb feeling state I thought,”Man that must’ve been close…”

“You’ve improved since St.Catherine’s,”Keller said in his heavily accented English as he slipped the silver medal over my head. “But not enough,” came his afterthought.

Peter Ayling, manufacturer of oars, wrote a supplement for the magazine ROWING, Oct./Nov. entitled: WELL DONE AMERICA. He wrote:

In training before the Regatta the press, in general, believed that it would be the East Germans who would push the West Germans. Some thought the Russians would make it a hard race for the Germans…it was considered that Harvard had “rowed above themselves” to trail West Germany by a mere five-second margin.

The opposition in the repechage probably gave the boys just what they needed: confidence against somewhat lower opponents, which allowed them to continue to improve as they had done throughout training… Although the manner of this win was impressive, it did not convince us that more than a fourth place seemed likely.

The last race arrived and the crowds became larger. At the 500 meter mark the margin of 1 1/2 seconds covered all six of the crews, but in the next quarter the picture changed dramatically and it was now 7 seconds which separated first from last with US in last-place. At the 1500 meter mark the American eight had made good 1 1/4 lengths overtaking Australia, East Germany, H olland and the R ussians. T he leaders, W est Germany , were only just a length in front. At the finish the US had closed to within a half length of a tiringWest Germany eight and then had kept her nose in front of Russia by .02 hundreds of a second. In the press box Robert Heron turned to me and said:“they should not do that too often, my heart won’t stand it.”